Audio Version

In the first episode of The Lonely Island (2001), Ardy, played by twenty-three year old Andy Samberg, all lips and shaggy curls, stars in a goofy early-90’s-hip-hop-MTV-style interlude. From the twin-sized bottom bunk on my ten-centimeter iPod screen, I studied this scene with adolescent gravitas.

This was my nightly routine: after allegedly going to sleep, I’d stay up watching every Andy Samberg video I could find. By knowing everything there was to know about him, I closed the distance between us. I emulated Andy’s expressions and gestures, but if people pointed out that I was trying to be like him, I’d deny it, chagrined. I wasn’t trying to be like him—I was trying to be him. The impossibility of that becoming left me heartbroken. I was born at the wrong time, I thought.

Andy grew up in the Bay Area in the 1980’s and 90’s, surrounded by sounds and aesthetics of hip hop and the experimental arts of San Francisco’s heyday, where nothing was off-limits. In 2005 he made it onto Saturday Night Live and popularized Digital Shorts, an up-and-coming medium distinct to the nascent chaos of Internet entertainment.

He was living the dream, my dream—he was the dream.

At a restaurant in Chicago where Andy had been interviewed, I ordered the kale salad (his order). It exacerbated my IBS, and I almost went to the hospital due to my obstructed bowels. Insufferable fiber included, I devoured all of the content related to Andy and anything remotely related to that. The shit built up. I took notes on artists like Nas and Xzibit, who influenced The Lonely Island’s obscene rap-parodies. I mail-ordered Berkeley High School’s Slang Dictionary, published long after Andy graduated. I saved the Samberg home number I’d found in the Berkley Whitepages, just in case. Just in case what? I wasn’t sure. But because it was possible, it felt necessary.

I fell in love with Andy at the start of my own adolescence, when the school hallways were awash with a smog of Axe and Abercrombie, sweaty bodies, and lunchboxes left in lockers overnight. I was largely uninterested in my own changing body: fuzzy legs which the tallest girl in my grade demanded I shave, the hard lump under my left nipple that hurt when it pressed against my seatbelt.

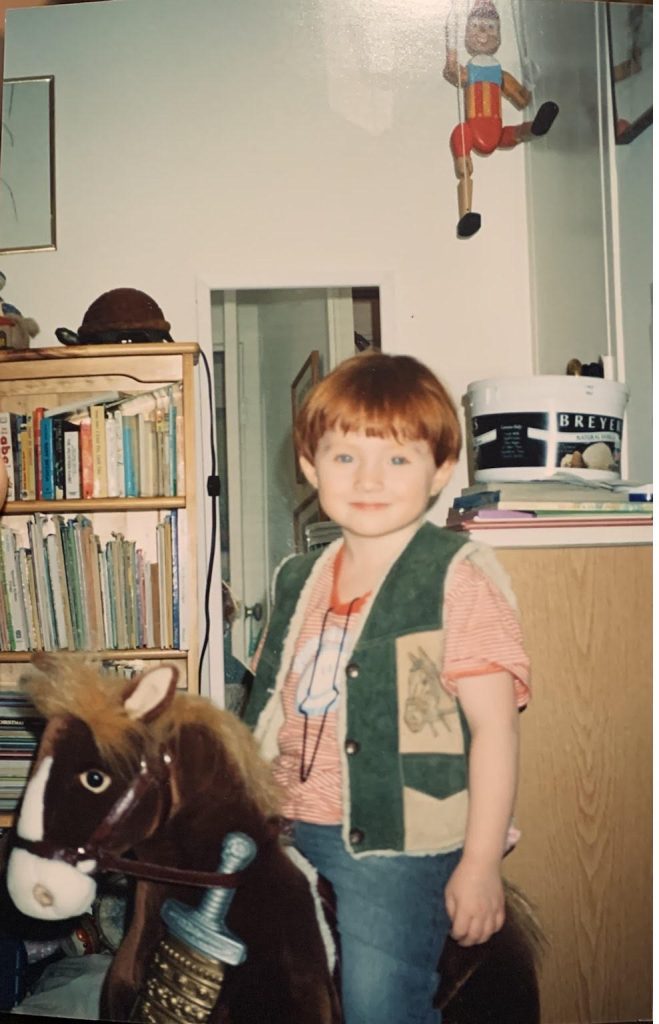

For all my life I’d cut my hair short and worn clothes from the boys’ section, passing, whether I liked it or not, as my mother’s grandson. This was the early 2000s, before trans children were a media phenomenon, and although I was surrounded by supportive adults, my obvious gender differences were never discussed in terms of potential transness, let alone medical options that might’ve helped me feel more at home in my body.

Instead, I managed the confusing process of growing from a boy into a woman. Like every adolescent, this meant coming to know a subjectivity defined at the violent expense of my imagination. If I couldn’t be whoever I wanted, what was I to become? I had no practice being a woman and no real desire to try. The clothes were tighter, fragrances sickeningly ambrosial. But because the changes seemed inevitable, reluctantly I grew out my hair, wore training bras, painted my nails grotesque neon hues, cut myself attempting to snip my leg hair with craft scissors, and asked out my best friend Owen, feeling that “dating” a boy would reaffirm my girl-ness in the eyes of the middle school public.

Meanwhile, I dreamt of being on SNL, and above all, being special to Andy. This unrequitable yearning became the object of my suffering, depression that I embraced as fuel for my art. I decided that I’d be the funniest class clown to ever live, but couldn’t articulate my underlying desperation to transmute into the man I loved, my destructive reverence for someone who’d never acknowledge me.

The burgeoning digital world allowed me to experience vicarious closeness that felt so real it was erotic. The Internet wasn’t yet everywhere, and thus felt hyper-personal, still replete with a novel and coveted randomness. I was sad but oddly hopeful then—only to become an adult in this apocalyptic world that isn’t at all funny, but is endlessly ironic.

Years later, walking down the austere hallway of my university, I heard a familiar voice. It was Jorma Taccone of The Lonely Island, best friend of the man I once loved! What were the chances of us crossing paths? Like a typical fan, I felt special. Are you Jorma? I blundered, knowing very well he was Jorma. I’d prepared for a moment like this for years, yet had no clue what to say. So I did as all fans must: requested a photo with my idol (or my idol’s best friend) which would forever pale in comparison to my dream of actual intimacy.

When the set up is long, they say the punchline better be good. Isn’t that the crux of transsexuality? To unabashedly close the distance between reality and our ideals? Before I knew I was trans, I was rapping every lyric to “Jizz in My Pants” on CD on the way to soccer practice, my mother’s grip on the steering wheel tightening as the hook repeated for the twelfth time. “Dick in a Box” doubled as moody morning music and my afternoon anthem. What did it mean that the soundtrack to my life was a phallocentric parody?

Nowadays, I’ve started wearing deodorants with names like “swagger,” and people tell me that I smell like their high school boyfriends. Queer eternal youth: a nightmare, a dream, a messy utopia. In the photo—now lost, data lodged in some impalpable cloud—I smile stupidly under bright overheads next to a hurried but generous Jorma. Later, I consider reviving my childhood dream of becoming a professional comic. I know it’s implausible, but I’ve been momentarily overtaken by an old love, fierce with juvenile import—part of me still adamant that I must commit to the bit.

Bio: Flip Zang (they/he) is a writer and historian born and living in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. They play the banjo and other music, and like to ask big questions. They can never decide which thing to love most.